Influence-based Attributions can be Manipulated

Influence Functions are a standard tool for attributing predictions to training data in a principled manner and are widely used in applications such as data valuation and fairness. In this work, we present realistic incentives to manipulate influence-based attributions and investigate whether these attributions can be systematically tampered by an adversary. We show that this is indeed possible for logistic regression models trained on ResNet feature embeddings and standard tabular fairness datasets and provide efficient attacks with backward-friendly implementations. Our work raises questions on the reliability of influence-based attributions in adversarial circumstances. Code is available at [https://github.com/infinite-pursuits/influence-based-attributions-can-be-manipulated](https://github.com/infinite-pursuits/influence-based-attributions-can-be-manipulated).

Introduction

Influence Functions are a popular tool for data attribution and have been widely used in many applications such as data valuation

Our Key Idea

Simply put, we show that it is possible to systematically train a malicious model very similar to the honest model in test accuracy, but has desired influence scores.

Setup

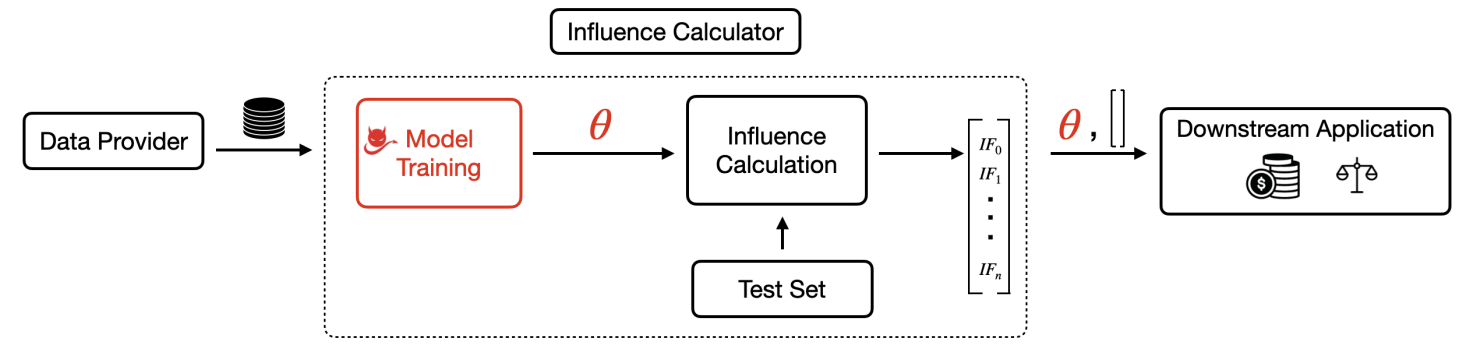

The standard influence function pipeline comprises of two entities: a Data Provider and an Influence Calculator. Data Provider holds all the training data privately and supplies it to the Influence Calculator. Influence Calculator finds the value of each sample in the training data by first training a model on this data and then computing influence scores on the trained model using a separate test set. We assume that the test set comes from the same underlying distribution as the training data. Influence Calculator outputs the trained model and the influence scores of each training sample ranked in a decreasing order of influence scores. These rankings/scores are then used for a downstream application. See figure on top of this blog for a pictorial representation of the setting.

Threat Model

We consider the training data held by the data provider and the test set used by the influence calculator to be fixed. We also assume the influence calculation process to be honest. The adversarial manipulation to maliciously change influence scores for some training samples happens during model training. To achieve this, the compromised model training process outputs a malicious model $\theta^\prime$ such that $\theta^\prime$ leads to desired influence scores but has similar test accuracy as original honest model $\theta^*$.

Data Valuation application with Targeted Attack

The goal of data valuation is to determine the contribution of each training sample to model training and accordingly assign a proportional monetary sum to each. One of the techniques to find this value is through influence functions, by ranking training samples according to their influence scores in a decreasing order

The canonical setting of data valuation consists of 1) multiple data vendors and 2) influence calculator. Each vendor supplies a set of data; the collection of data from all vendors corresponds to the fixed training set of the data provider. The influence calculator is our adversary who can collude with data vendors while keeping the data fixed.

Goal of the adversary. Given a set of target samples $Z_{\rm {target}} \subset Z$, the goal of the adversary is to push the influence ranking of samples from $Z_{\rm {target}}$ to top- $k$ or equivalently increase the influence score of samples from $Z_{\rm {target}}$ beyond the remaining $n-k$ samples, where $k \in \mathbb{N}$. Next we propose targeted attacks to achieve this goal.

Let us first consider the case where $Z_{\rm {target}}$ has only one element, $z_{\rm {target}}$ and propose a Single-Target attack. We formulate the adversary’s attack as a constrained optimization problem where the objective function, $\ell_{\rm {attack}}$, captures the intent to raise the influence ranking of the target sample to top- $k$ while the constraint function, $\rm {dist}$, limits the distance between the original and manipulated model, so that the two models have similar test accuracies. The resulting optimization problem is given as follows, where $C \in \mathbb{R}$ is the model manipulation radius,

$\min_{\theta^{\prime}:\rm {dist} (\theta^*, \theta^{\prime}) \leq C} \ell_{\rm {attack}} (z_{\rm {target}}, Z, Z_{\rm {test}}, \theta^{\prime})$

When the target set $Z_{\rm {target}} \subset Z$ consists of more than 1 sample, we can simply re-apply the above attack multiple times, albeit on different samples. The primary challenge with these attacks is that calculating gradients of influence-based loss objectives is highly computationally infeasible due to backpropagation through hessian-inverse-vector-products. We address this challenge with a simple memory-time efficient and backward-friendly algorithm to compute the gradients while using existing PyTorch machinery for implementation. This contribution is of independent technical interest, as the literature has only focused on making forward computation of influence functions feasible, while we study techniques to make the backward pass viable. Our algorithm brings down the memory required for one forward $+$ backward pass from not being feasible to run on a 12GB GPU to 7GB for a 206K parameter model and from 8GB to 1.7GB for a 5K model.

Experimental Results

All our experiments are on multi-class logistic regression models trained on ResNet50 embeddings for standard vision datasets. Our results are as follows.

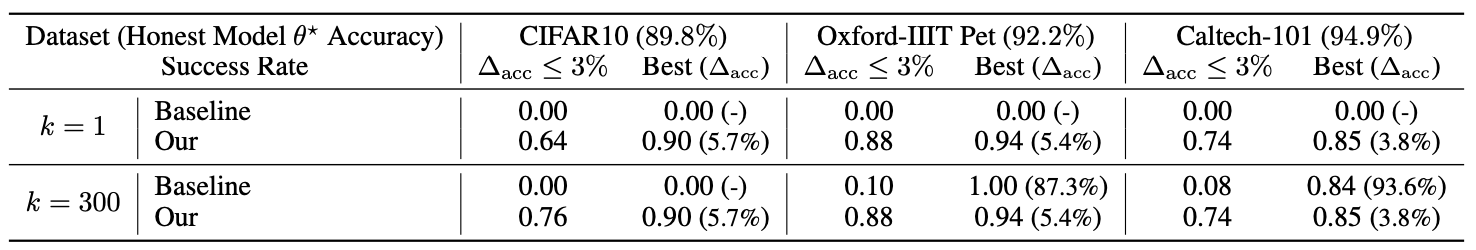

- Our Single-Target attack performs better than a non-influence Baseline.Consider a non-influence baseline attack for increasing the importance of a training sample : reweigh the training loss, with a high weight on the loss for the target sample. Our attack has a significantly higher success rate as compared to the baseline with a much smaller accuracy drop under all settings, as shown in the table below.

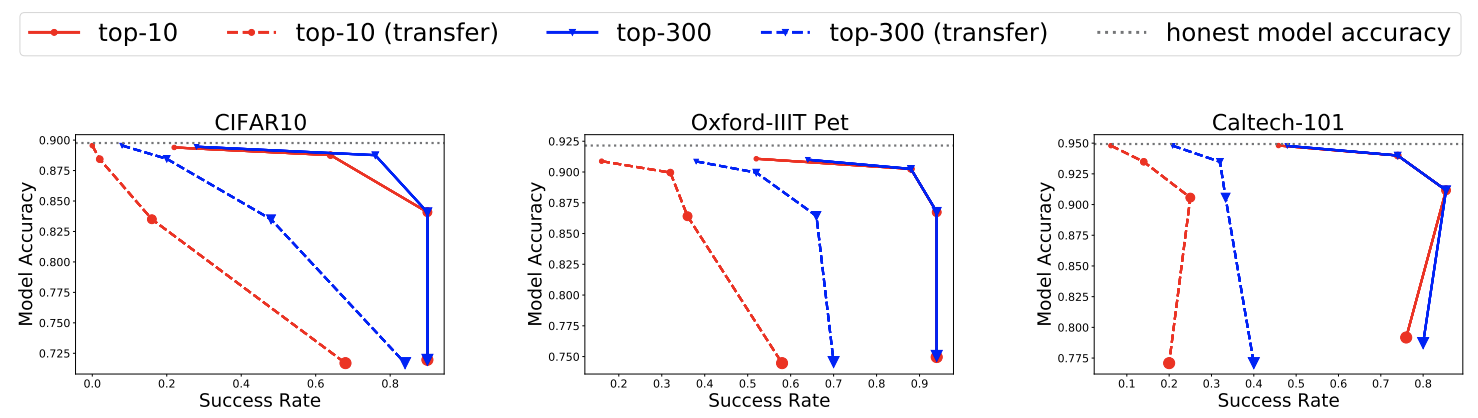

- Behavior of our Single-Target attack w.r.t manipulation radius $C$ & training set size. Theoretically, the manipulation radius parameter $C$ in our attack objectives is expected to create a trade-off between the manipulated model's accuracy and the attack success rate. Increasing radius $C$ should result in a higher success rate as the manipulated model is allowed to diverge more from the (optimal) original model but on the other hand its accuracy should drop and vice-versa. We observe this trade-off for all three datasets and different values of ranking $k$, as shown in the figure below. We also anticipate our attack to work better with smaller training sets, as there will be fewer samples competing for top- $k$ rankings. Experimentally, this is found to be true -- Pet dataset with the smallest training set has the highest success rates.

- Our attacks transfer when influence scores are computed with an unknown test set. When an unknown test set is used to compute influence scores, our attacks perform better as ranking $k$ increases, as shown in the figure above. This occurs because rank of the target sample, optimized with the original test set, deteriorates with the unknown test set and a larger $k$ increases the likelihood of the target still being in the top-$k$ rankings.

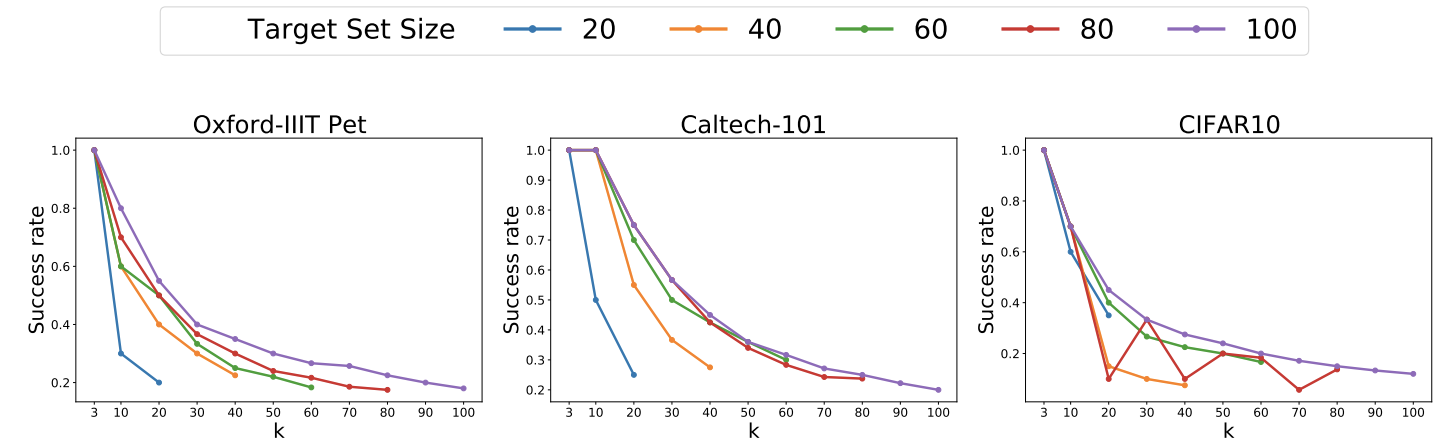

- How does our Multi-Target Attack perform with changing target set size and desired ranking $k$? Intuitively, our attack should perform better when the size of the target set is larger compared to ranking $k$ -- this is simply because a larger target set offers more candidates to take the top-$k$ rankings spots, thus increasing the chances of some of them making it to top- $k$. Our experimental results confirm this intuition; as demonstrated in the figure below, we observe that (1) for a fixed value of ranking $k$, a larger target set size leads to a higher success rate; target set size of $100$ has the highest success rates for all values of ranking $k$ across the board, and (2) the success rate decreases with increasing value of $k$ for all target set sizes and datasets. These results are for the high-accuracy similarity regime where the original and manipulated model accuracy differ by less than $3\%$.

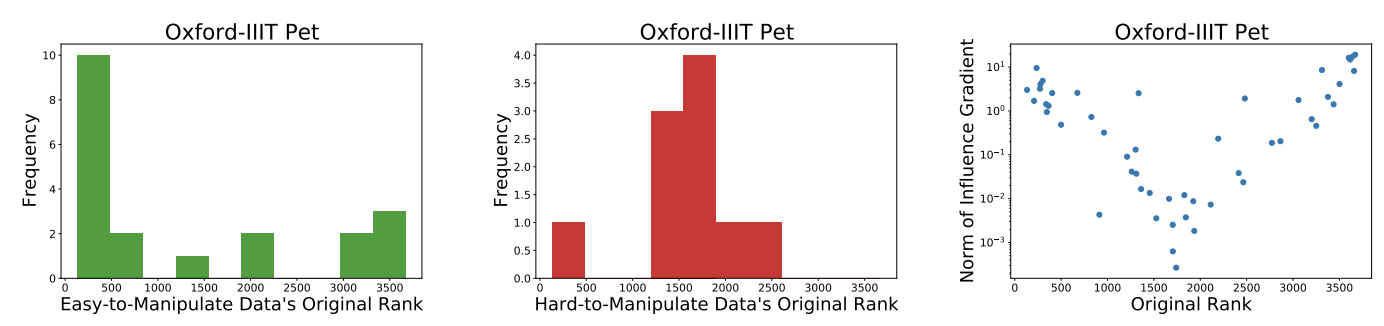

- Easy vs. Hard Samples.We find that target samples which rank very high or low in the original influence rankings are easier to push to top-$k$ rankings upon manipulation (or equivalently samples which have a high magnitude of influence either positive or negative). This is so because the influence scores of extreme rank samples are more sensitive to model parameters as shown experimentally in the figure below, thus making them more susceptible to influence-based attacks.

- Impossibility Theorem for Data Valuation Attacks. We observe that even with a large $C$, our attacks still cannot achieve a $100\%$ success rate. Motivated by this, we wonder if there exist target samples for which the influence score cannot be moved to top-$k$ rank? The answer is yes and we formally state this impossibility result as follows. Theorem 1:For a logistic regression family of models and any target influence ranking $k\in\mathbb{N}$, there exists a training set $Z_{\rm train}$, test set $Z_{\rm test}$ and target sample $z_{\rm target} \in Z_{\rm train}$, such that no model in the family can have the target sample $z_{\rm target}$ in top- $k$ influence rankings.

Kindly check the paper for ablation study on our attack objective and more details on the experiments.

Fairness Application with Untargeted Attack

Recently influence functions have been proposed to increase the fairness of downstream models

We propose an untargeted attack for this use-case : scale the base model by a positive constant. The malicious base model output by the model trainer is now a scaled version of the original model. Note that for logistic regression the malicious and original base model are indistinguishable since scaling with a positive constant maintains the sign of the predictions, leading to the same accuracy.

Experimental Results

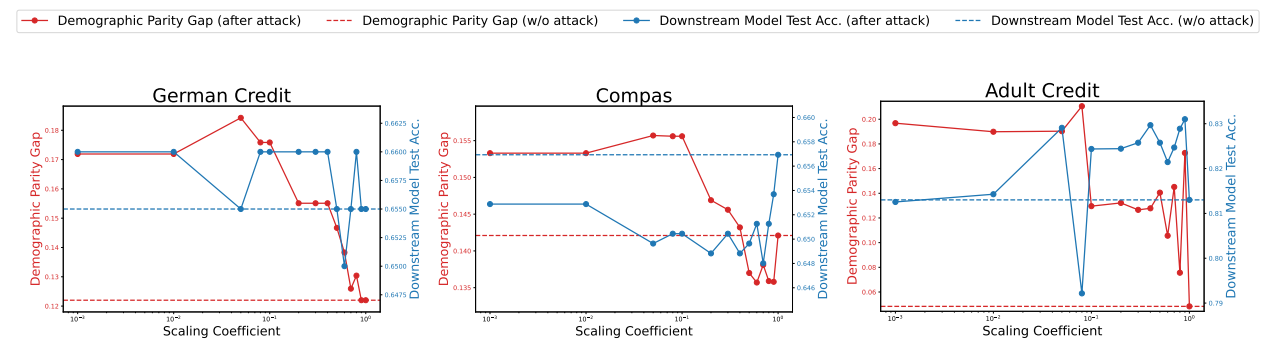

All our experiments are on logistic regression models trained on standard fairness datasets. We measure fairness with demographic parity

As can be seen from our results in the figure below, the scaling attack works surprisingly well across all datasets – downstream models achieved after our attack are considerably less fair (higher DP gap) than the models without attack, achieving a maximum difference of 16$\%$ in the DP gap. Simultaneously, downstream models post-attack maintain similar test accuracies to downstream models without attack. Since the process to achieve the downstream model involves a lot of steps, including solving a non-convex optimization problem to find training data weights and then retraining a model, we sometimes do not see a smooth monotonic trend in fairness metric values w.r.t. scaling coefficients. However, this does not matter much from the attacker’s perspective as all the attacker needs is one scaling coefficient which meets the attack success criteria.

Discussion on Susceptibility and Defense

The susceptibility of influence functions to our attacks can come from the fact that there can exist models that behave very similarly (Rashomon Effect

Conclusion

While past work has mostly focused on feature attributions, in this paper we exhibit realistic incentives to manipulate data attributions. Motivated by the incentives, we propose attacks to manipulate outputs from a popular data attribution tool – Influence Functions. We demonstrate the success of our attacks experimentally on multiclass logistic regression models on ResNet features and standard tabular fairness datasets. Our work lays bare the vulnerablility of influence-based attributions to manipulation and serves as a cautionary tale when using them in adversarial circumstances. Some other future directions include manipulating influence for large models, exploring different threat models, additional use-cases and manipulating other kinds of data attribution tools.

For code check this link : https://github.com/infinite-pursuits/influence-based-attributions-can-be-manipulated

For the paper check this link : https://arxiv.org/pdf/2409.05208

For any enquiries, write to : cyadav@ucsd.edu